I was entranced by Danielle Roberts’ paintings included in the new exhibition “Phosphorescence And Gasoline” at Fredericks & Freiser in New York City before I even fully grasped what was unfolding within them.

The figurative and highly expressive works were lit, in large part, by unnerving, unnatural, and unearthly light. Familiar cues of our lived spaces out here in the three-dimensional world were left to loom as perceptual signposts that obscured rather than clarified.

Darkness & Light in Roberts’ Paintings

Roberts’ painted scenes, frequently set at night or indoors so it’s at least unclear what time of day it is, were awash with darkness that battled it out with a bathroom light fixture, a bar’s dim lighting, or a somehow lackadaisically hanging disco ball… but everything remained strikingly clear. The colors within each scene popped with off-kilter, internal light that felt consumptive or at least gnawing, starkly contrasted with the consistently reappearing, background darkness.

In Roberts’ “Tomb of a Time” (2024), in which the painting’s vantage point looks at a house party through glass doors, the painter constructed participating figures’ faces with forms of a jarring and nearly searing kind of dirty neon.

The dance of lighting across Roberts’ paintings was often aggressively — through bewitchingly — unsettled. “Drawn from the Night” (2024) positions the viewer behind a figure apparently heading to a pub, which is lit like an ominous beacon against an encroaching, nighttime darkness. And as it stands there alone against a wooded backdrop, the pub and its lighting also feel encroaching: an expanding, enveloping cloud building upon itself, cultivating a maybe irresistible draw, for better or for worse.

Roberts blends her characters with their environments, which all together hang somewhat erratically. The scenes are constantly switching back and forth between the clear and recognizable and the slowly dissolving, like the first moments of everything sliding together in a haze. It’s a tsunami of information and possibility — food and drink reappear throughout the exhibition — beset by unmet promises. It reminds me of our contemporary dilemma in which information is relentlessly accessible but ignorance persists.

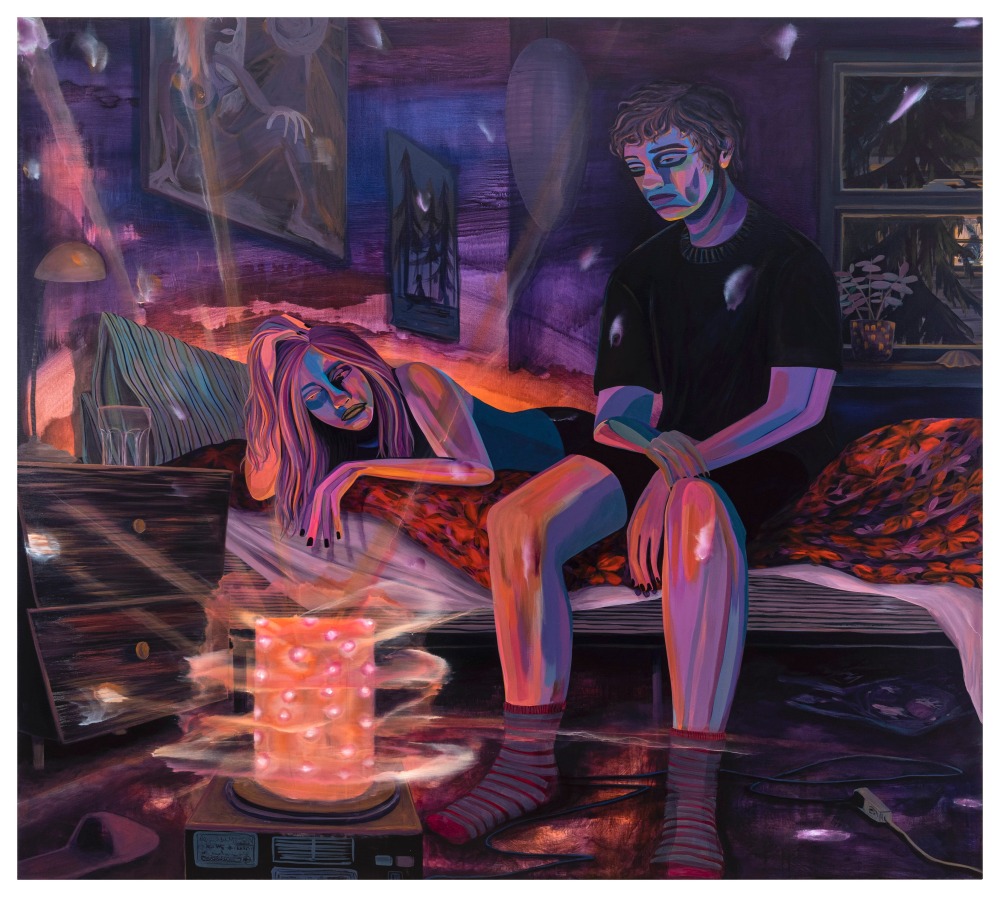

“Dream Machine” (2024), in which two figures sit stoically on a bed and gaze into an artificial light fixture on the floor in front of them, and “Holy Void” (2024), in which a few figures (again with their backs to us) try and get something out of an oddly illuminated vending machine, both come with similar connotations. These characters look besotten by a spell, playing out a routine perhaps set in motion by someone else entirely. They’re decisions teed up by the options in front of you.

Stuck, Gazing into the Light

When I first visited the exhibition, one thing really stuck out to me in just about every painting. Figure after figure and scene after scene looked stuck in a jarring stasis. Forms, characters, and scenery looked visually at odds with each other… and stayed there.

The most movement that I felt in the paintings came from that relentless, internal light that seemed ready to develop just a little further and consume whatever it was touching, something perhaps just moments away. With the heightened colors and the forms that looked ready to slip beyond recognition, these paintings landed like they were teetering on the edge of their inhabitants becoming subsumed by the combination of that internally driven light and whatever was within that ensnaring step away from it in the darkness.

The visual construction of these paintings looked like perhaps familiar, real-world scenes subjected to erosion. There was a lot of staring.

In many of these paintings (a few tended instead towards something more mythical), everything/everyone was left to simply… look at each other, or at actually no one at all. Again and again, it’s a story of standing, or sitting, or lurking, or watching. The lights towards which characters gaze or move seem oriented more towards consumption than enlightening illumination.

Because despite all the looking, you get the sense of a yawning chasm opening up either just around the corner, with everyone and everything trying to ignore it, or right in front of you, like in “Drawn from the Night,” where in terms of what’s actually happening on the canvas, it’s unclear that the central figure is actually moving at all. They might just be standing there, with both the light and the darkness at a distance.

In that disco ball scene, the bar is mostly empty.

Internal Light

Roberts’ characters look like they’re waiting, and the scenery around them looks like it’s waiting too, while nobody and nothing knows what precisely is meant to show up. The forms of Roberts’ exhibited paintings all start up and then slowly drift away.

Held in isolation, the restaurant, the bar, the dance floor, and the bathroom — among other spots — become not a question but a slowly crushing inevitability.

For everything that I just said and the parallels to contemporary struggles — particularly those of young adults (all the characters in Roberts’ paintings looked like they were in their 20s-30s, to me), I do think there’s an opening for optimism here, and it’s that internal light defining Roberts’ unique color palette.

There’s something left inside that, if brought into fruition, could outline a more uplifting arc. And honestly, it’s deeply beautiful how even against the crush of encroaching, domineering inevitability, there are still moments in these paintings of connection and camaraderie.

In “Community Spirit” (2024), it looks like someone’s being taken to the airport. (There’s a big sign that says “terminal,” though Roberts’ scenes tend not to be photorealistic to the point of providing a lot more specific details.) Two figures appear to be returning to a third waiting at their car, fast food haul for the three of them in hand. And they might all three be beset by those internal spirals and background darkness, but they’re clearly together — oriented across the canvas to suggest real unity, as the title posits.

“Danielle Roberts: Phosphorescence And Gasoline” continues at Fredericks & Freiser through December 7, 2024.